17 May 2013

Update : Here’s a discussion of this post on Reddit, and here is a French translation.

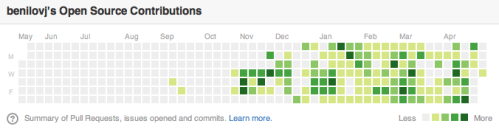

I’m a developer. Here’s the graph of my open source contributions on GitHub for the last 12 months:

(green squares signify days when I’ve made commits to open-source repos)

(green squares signify days when I’ve made commits to open-source repos)

While I also do some open source in my spare time, the vast majority of those green dots happen during my work at the Government Digital Service (GDS), a team inside the UK Cabinet Office.

I’m not some special case in my team - if you look at GDS’s GitHub organisation, you’ll see loads of code there. Better still, our work doesn’t just happen at the fringes of government IT - we’re responsible for the GOV.UK website, which is the UK central government’s main publishing platform and the front door to all government transactions.

One point where I have perhaps exaggerated: as James Stewart, one of GDS’s technical architects, points out, what GDS does is actually “coding in the open”, rather than “open source” - this means that GDS makes the source available under an OSS license, but doesn’t support or build communities around it. In any case, even “coding in the open” is awesome for a number of reasons.

fairness towards the taxpayer

Government source should be open - after all, if the code was written on the taxpayer’s dime, it’s only fair that the taxpayer gets the code in return. Interestingly, criterion 15 in the recently published Digital by Default Service Standard should institutionalise this and ensure that all future UK government projects will be mandated to open up their source by default:

Make all new source code open and reusable, and publish it under appropriate licences (or have provided a convincing explanation of why this cannot be done for specific subsets of the source code)

We use open-source languages and frameworks (most of GOV.UK is written in ruby and scala), open source web servers, manage our source and configuration using open source tools (git and puppet), and deploy onto open source operating systems (running linux). It’s only fair that we give back.

transparency

Having GDS’s code on GitHub makes my life as a GDS dev easier. If I need to integrate with, reuse or extend another GDS component, it’s just a few clicks in the browser or quickly cloning the repo.

The transparency also benefits those outside of GDS. Want to the rules for the state pension calculator? Just look at its source. Found a bug with the bank holidays page? You can submit a pull request to fix it.

I know of companies that have internal open source programs, and that’s definitely a step in the right direction, but having pretty much everything available brings the ideal of collective code ownership that much closer.

As an added bonus, since all the hacks and shortcuts would be there for everyone to see, less corner cutting is a natural consequence.

reuse

While a fair amount of the code we write is solving problems unique to our domain, large parts of it is general, and could easily be adapted for in other central, state and local governments, or in the private sector. In fact, people are starting to do that already. What some good front-end code? Check this out. Want a government-grade single-sign-on system? Here you go. Want to build your own smart answers? Knock yourself out.

marketing

Coding in the open is great marketing for the GDS brand. When I tell other hackers that I do open source at work, eyebrows go up. I’ve heard people outside GDS refer to it as the “government startup”; open source clearly enhances the brand.

as a portfolio

For purely selfish reasons, it’s really nice to have a portfolio of my work, somewhere I can point people to for tangible proof of my (in?)ability to write ruby.

I wish more employers did this (and not just in the public sector) - if yours doesn’t, perhaps the reasons above can help convince them to change their mind?

14 Apr 2013

Update : this post kicked off a lively debate over at HackerNews.

As a result of doing consulting, I’ve been hopping between a large number of OSS tools and libraries for the past few years. At some point, I decided to start giving back (after taking so so much) - something that GitHub has made incredibly easy, at least in the technical sense. For the most part, my interaction with maintainers has been very professional, effective and pleasant, but has also gotten under my skin enough times for me to want to post about it.

So, a plea to the OSS maintainers out there.

You would make my coding life much much happier, if:

1) You could always have the courtesy to acknowledge the bug or pull request I’ve submitted.

By the time you’ve got an issue notification from GitHub, I have already:

- Hit and investigated a problem with your project

- Trawled the forums/Stackoverflow/bug tracker for a fix

- Documented the bug, context, testcase etc

For a pull request (PR), I’ve had to do even more legwork, ie:

- Slug through your (not always the most obvious in the world) code

- Figure out your coding conventions

- Create a working fix

- Update or write new tests

- Update docs

- Document the PR

So, if I haven’t provided enough context or information or test coverage, say so. I’ve invested time already, I don’t mind spending a bit more to get the change over the line.

If you’re no longer maintaining the project, say so. That’s cool too, perhaps I can hopefully find somebody who has continued your work.

If you have crunch time in your day job, are moving house and going to your gran’s for 3 weeks, just set the expectation that you won’t have time to look at this for a month.

If you think that the proposed change doesn’t fit the direction of the project, or the bugfix is in the ‘nice to have’ pile on your backlog, say so. I might not have gotten the result that I wanted, but at least I would have closure.

In the very least, say SOMETHING , so I don’t feel angry and annoyed that I spent all this time and effort for nothing.

Besides, if you or your company are keen to benefit from community contributions, a bunch of unacknowledged year-old PRs lying around probably isn’t the best way to achieve that.

2) You could merge tiny changes quickly

The killer GitHub + Travis combo leaves little excuse for slow merging of very small, safe changes (ie small refactorings or documentation typos) - I’ve been able to accept changes during my train commute on my phone over a dodgy 3G connection. Nowadays, before any non-trivial contribution to a new project, I tend to raise a tiny PR first. The time it takes for this PR to be merged informs my decision on whether or not to expend effort on the larger change.

3) You could apply a two-step process for reviewing bigger changes

If an issue needs time to investigate or to analyse, you could acknowledge it first (see 1)) and set expectations on when the investigation/analysis would take place. Then take the time you need. This way, you don’t leave the submitter in limbo.

4) You would not forget to thank people for their time and effort.

It’s easy to do and does make a difference.

Yes, I know, most maintainers do open source in their free time, but the same is true for the submitters. Just some simple changes could make the experience that bit more fun for everyone.

29 Mar 2013

I am pleased to announce the release of DbFit 2.0.0 RC4. The ZIP archive can be downloaded from the DbFit homepage.

The highlights of this release:

You can find more details on the “What’s new” page.

A huge thanks goes to:

- Yavor Nikolov for doing almost all of the Oracle work for this release, as well as code reviews and feedback

- Christian Krämer for a lot of the behind-the-scenes work to port DbFit from Maven to Gradle

21 Mar 2013

At this moment (March 2013), there are 4 different distributions of the DbFit project in the wild. In this post, I hope to give some background as to why this is so and which version to use when.

The original DbFit

In 2007, Gojko Adzic released the original version of DbFit, a set of .NET fixtures for FitNesse for interacting with the database. The fixtures were later ported to Java, and the list of supported databases also grew with time. The last released version of the original DbFit is the 1.1 version; it is still available on SourceForge.

Post 2008

Since 2008, the original project did not see any active development, although the tool continued being downloaded and used by many teams ever since. As a result, the DbFit code was “donated” into two projects: the .NET fixtures made their way into FitSharp, maintained by Mike Stockdale and the Java fixtures were ported and added to FitLibrary, which is maintained by Darren Rowley. While both versions received small changes and bug fixes, it is my understanding that they remained fundamentally unchanged from the last original 1.1 release.

Fast forward to 2013

In January of this year, I restarted active development on the DbFit codebase on GitHub. Before Gojko had moved on to greener pastures, he was working on the 2.0 release, so I used this as the starting point. My first goal was to consolidate:

- to release a binary distribution that worked with the latest and greatest version of FitNesse

- to update and improve the documentation and user experience of the current feature set

- fix any problems that had quick and easy solutions

- to try to kickstart the community and improve the knowledge sharing amongst those currently using the tool

So far, all changes made by myself and the recent contributors (thanks guys!) has been to the Java source. In fact, I’ve dumped the original .NET code from GitHub and distribute the FitSharp v2.2 fixtures with the DbFit 2.0 binaries. I would definitely like to port the Java changes to FitSharp at some point, but that isn’t happening right now, so unless something specific is needed (please get in touch directly or on the forum if that’s the case), that isn’t high on the priority list at the moment.

Hopefully, the 2.0 final release will be pushed out in April. After that, the focus would be on adding features (support for more databases and ETL tools, improvements to the documentation, refinements to the test tables, making DbFit play nicely with Slim and FitLibrary).

Which DbFit to use?

So, that’s an overview of all the projects, now which version should you use and when?

DbFit 1.1 - there isn’t any reason to use this now. It’s been superseded by DbFit 2.0.

FitSharp 2.2 - you can use this version if you need database access in your FitSharp tests under Windows (however I’ve bundled FitSharp 2.2 into the DbFit 2.0 release candidates).

FitLibrary 2.0 - use this if you need database access in your FitLibrary-based tests and you don’t want a dependency on Fit.

DbFit 2.0 - This is the only version that bundles a working, already wired combination of FitNesse and DbFit. However, if you have an existing FitSharp or FitLibrary setup, you probably won’t get a great benefit from using this just yet.

26 Feb 2013

I am pleased to announce the release of DbFit 2.0.0 RC2. The ZIP archive can be downloaded from the DbFit homepage.

What’s included in this release?

- DbFit upgraded to FitNesse release v20130216:

- WISYWIG editor: multiline cell editing bugfixes.

- DbFit now bundled with FitSharp 2.2 (.NET 4.0). This:

- allows combining DbFit and .NET fixtures in the same test

- expands database supports in .NET mode to MS Sql Server, Oracle, MySQL and Sybase

- Support for the Oracle NCLOB datatype (issue #14).

- The DbFit Acceptance Test pages have been moved to a subwiki (issue #15).

In addition, some of the original manual has been extracted and posted online since the RC1 release.

What’s coming next

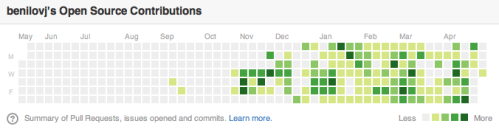

(green squares signify days when I’ve made commits to open-source repos)

(green squares signify days when I’ve made commits to open-source repos)